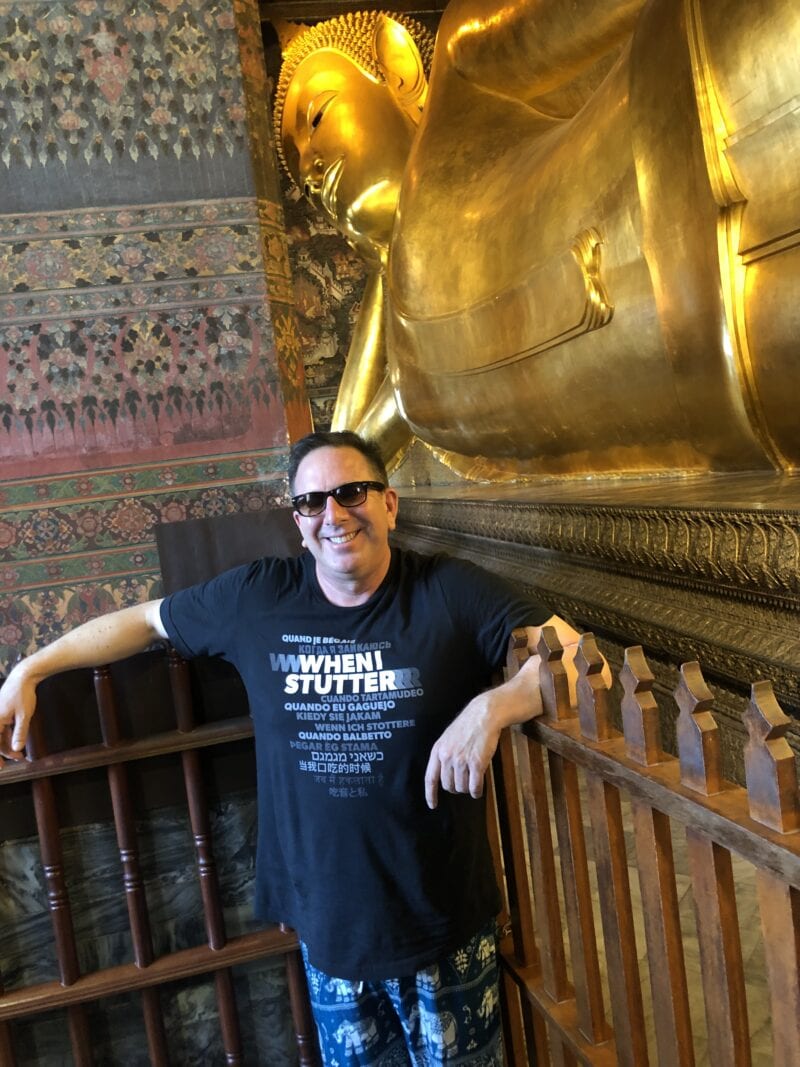

DENNIS FULGONI

Dennis Fulgoni has been one of my best friends for years and one of the most positive forces in my life. He had been hearing me talk about WHEN I STUTTER long before I ever started working on it. Being a creative person himself, he would often provide me with the exact right words at just the right time.

After post-production had begun, there were some long stretches where the film wasn’t being worked on. In these moments I often felt stuck and truly lost. He explained to me that artists often get stuck in the “muddle” which is this stage in-between the beginning and end where one can’t see the light from either end of the tunnel. He told me to “keep going” and I did…

Dennis watched many versions of the film and gave me encouraging and honest feedback. Somehow, he was always spot on with his observations- he truly has a talent for seeing the big picture. He is credited as a writer in the film because his suggested rewrites always made the narrative portions flow better. Another fun fact is that he performed the “head encased in plaster” role which appears in the final narrative portion of the film.

I must say that the last 5 years of my life have been some of the best, creatively and otherwise. Everybody out there needs a friend and “partner in crime” like Dennis Fulgoni. The only thing that eclipses that big brain of his is the size of his heart.

When I notice someone stuttering, or someone tells me they stutter, my empathy is super deep; but more importantly, I see this person’s strength in a new way. How special they are.

What has been the response from others about the film?

The response has been overwhelmingly positive. I’ve shown it to many of my friends and co-workers (I’m a principal), and without fail people are blown away by the film. The thing I hear people say most is how moved they are by the experience. How much it spoke to them, whether they stuttered or not. My girlfriend, I remember, cried, and that is not her usual response to a documentary film.

You helped write portions of the film and you also helped make some creative decisions. Can you speak to that experience?

John got me on board to help write parts of the narration. I tried to make the narration flow better, to be more conversational. It was interesting because coming into the project I didn’t have much working scientific knowledge of stuttering. But writing some of these sections gave me deeper understanding of the physical and psychological complexities of it. This in turn helped me quite a bit with the creative decisions I suggested or, more often, critiqued. I was kind of a sounding board for John, and although I’m not a filmmaker or a speech pathologist, I am a storyteller so I tried to approach my critiques from that angle. John and I talked quite a lot about the through-line of the story, and the universal appeal he was striving for. It was a joy to watch the film emerge.

What was your favorite or most memorable part of the process of making the film?

Definitely watching the different drafts, how they made each viewing better. John and I might watch the film, talk about things, and then he’d go off and work tirelessly and make all these changes and he’d have me watch another version and I was amazed at how much better it got each time. It was like watching a sped-up version of evolution. That was really enjoyable and a testament to John’s work ethic.

What has surprised you about the film since it was first presented?

Definitely the number of places it’s played. Literally all over the world. I told John early on–when he himself was doubting the project–I had a feeling about it. I thought it was a gem, and was going to be great. But I couldn’t have imagined the success it’s actually achieved. Right after he finished a solid draft we, rather spontaneously, took off to Iceland to celebrate. It was a special trip and one I will remember always. And then, a couple years later, John tells me the film is playing in Iceland. He ended up on the national news there. That was full circle, and very, very sweet.

Your son (Lel) plays a young Barry Guitar in the film. Can you or Lel share some thoughts about that experience?

Lel is sitting with me right now, so let’s ask him. He says, “It was an experience I didn’t expect to have and at first I was nervous. It made me feel like I was transported back in time. It was good to play a younger version of a character who would appear as his older self in the film. When I saw myself on the big screen, I was blown away. It’s really something to see yourself up on the big screen and people laughing and enjoying your scene. I felt a little like a star.” As a father, it made me proud to see my son involved in a film in which I too had a part. It made me feel artistically close to him. And a little jealous of his star-like quality.

As a person who does not stutter, how has your perception of people who stutter changed?

I’m certainly more empathetic. And aware. I notice stuttering all the time now. It’s amazing I didn’t register it as much before this film. When I notice someone stuttering, or someone tells me they stutter, my empathy is super deep; but more importantly, I see this person’s strength in a new way. How special they are. I feel almost a kinship with them in a way I don’t think I did before. It’s been a quite beautiful experience.

What’s changed in your life since the film was first presented? Written any books?

In fact, I wrote a novel set during the Night Stalker killings. It’s currently with an editor in New York, and I’m super jazzed about seeing where this project will go next.

Purchase WHEN I STUTTER to watch

19 compelling individuals

talk about their journey with stuttering.